The Science of Happy Plants: What Your Garden Is Trying to Tell You

Plants don’t speak our language, but they are constantly communicating through their biology. Mastering the science of happy plants is about learning to decode the visual signals your garden sends when its needs aren't being met.

By observing the subtle shifts in colour, texture, and posture, you can intervene before a minor stressor becomes a fatal problem.

Click on the following links to learn more.

Gauld Nurseries is your go-to destination for happy plants.

Let us help you lay the groundwork for a beautiful garden in 2026..

Key Takeaways

Yellow leaves often point to overwatering or a lack of nitrogen.

Brown, crispy tips are usually a sign of low humidity or mineral buildup.

Drooping is caused by a loss of turgor pressure, often due to underwatering.

Slow growth typically suggests the plant isn't getting enough light to fuel photosynthesis.

Regular observation is the best preventative medicine for any garden

1. The Yellow Leaf Mystery

When a leaf loses its green pigment, it is a sign that chlorophyll production has stalled or that existing chlorophyll is being broken down. However, not all yellowing is created equal. To diagnose the issue, you must look at where the yellowing starts and how it spreads.

Mobile vs. Immobile Nutrients

The most critical scientific distinction in plant care is whether the missing nutrient is "mobile" or "immobile." This determines where the symptoms first appear.

Mobile Nutrients: These are the "freelancers" of the plant world. If the plant isn't getting enough from the soil, it will physically harvest these elements from its older, bottom leaves to feed the new, emerging growth. This is why a nitrogen deficiency manifests as yellowing at the base of the plant first.

Immobile Nutrients: These elements are "locked" into the leaf structure once they arrive. If the plant runs out, it cannot move them from old leaves to new ones. Consequently, the new growth at the top will emerge yellow or stunted, while the old leaves remain green.

The Chemistry of "Nutrient Lockout"

Sometimes, your soil is packed with nutrients, but your plant is still turning yellow. This is often due to Nutrient Lockout caused by an improper pH level. If the soil is too acidic or too alkaline, chemical reactions occur that bind the nutrients to soil particles, making them "invisible" to the plant's roots.

For most garden plants, a pH between 6.0 and 7.0 is the "sweet spot" where nutrients are most soluble.

The Role of Oxygen and Turgor

Overwatering is the leading cause of yellowing for indoor gardeners, but the reason is often misunderstood. It isn't the "extra water" that kills the plant; it's the lack of oxygen. When soil is perpetually saturated, the air pockets (macropores) are filled with water, creating an anaerobic environment.

Without oxygen, the roots cannot perform cellular respiration, causing them to rot and stop transporting the water and minerals needed to keep leaves green.

| Symptom Pattern | Likely Scientific Cause | Immediate Action |

|---|---|---|

| Old leaves turn yellow first | Nitrogen (N) Deficiency (Mobile Nutrient) | Apply a high-nitrogen organic fertilizer. |

| New leaves are yellow, veins stay green | Iron (Fe) Deficiency / High pH (Immobile Nutrient) | Test soil pH and apply chelated iron. |

| Yellowing with "mushy" stems | Root Hypoxia (Overwatering/Lack of Oxygen) | Repot in well-draining soil and check for root rot. |

| Interveinal yellowing (veins stay green on old leaves) | Magnesium (Mg) Deficiency | Apply a diluted Epsom salt solution (MgSO4). |

By identifying whether the yellowing affects old or new tissue, you can pinpoint exactly which chemical element your plant is craving.

2. Crispy Edges: The Battle with Humidity and Salt

When the perimeter of a leaf turns brown and brittle, you are witnessing a failure in the plant’s hydraulic system. This usually happens at the "ends of the line"—the leaf tips and margins—where the plant's vascular system (the xylem) has the hardest time delivering water.

The Physics of Transpiration and VPD

Plants don't just "drink" water; they are pulled by the atmosphere. This process is called transpiration. Through tiny pores called stomata, plants release water vapour into the air. This creates a vacuum effect that pulls more water up from the roots.

However, the speed of this "pull" is dictated by the Vapour Pressure Deficit (VPD)—the difference between the amount of moisture in the air and how much moisture the air could hold if it were saturated.

High VPD (Hot, Dry Air): The air is "thirsty" and rips moisture out of the leaves faster than the roots can replace it. This causes the cells at the edges to collapse and die, resulting in "crispy" tips.

The Fix: Lower the VPD by increasing local humidity (using a humidifier or grouping plants) or lowering the temperature.

Osmotic Stress and Salt Accumulation

The second cause of crispy edges is chemical. If you use tap water high in minerals (calcium, magnesium, or chlorine) or over-fertilize, these salts accumulate in the soil.

Through osmosis, water naturally moves from areas of low salt concentration to high salt concentration. If the soil becomes saltier than the plant’s roots, the soil actually starts "pulling" water out of the plant.

This is known as physiological drought. The plant tries to push these excess salts as far away from its vital organs as possible, depositing them at the leaf tips, which eventually "burns" the tissue.

Regularly flushing your pots with distilled or rainwater ensures that harmful mineral salts don't reach toxic levels in the root zone.

| Symptom | Scientific Mechanism | The Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uniform Brown Tips | High Vapour Pressure Deficit (VPD) causing rapid transpiration. | Increase humidity to 50%+ and move away from heat vents. |

| Crusty White Soil/Edges | Osmotic Stress due to mineral/salt buildup in the substrate. | Flush the soil with a volume of water 3x the size of the pot. |

| Yellow-to-Brown Margins | Potassium (K) Deficiency affecting water regulation in stomata. | Apply a potassium-rich organic fertilizer or seaweed extract. |

| Sudden Brittle Leaves | Thermal Stress (Direct Cell Membrane Damage). | Identify "hot spots" where sun is magnified by window glass. |

3. The Sag and the Curl: Understanding Turgor Pressure

In the science of happy plants, "turgor pressure" is the gold standard of health. This is the force of the water inside the plant cell pushing against the rigid cell wall. When a plant is well-hydrated, its cells are "turgid"—firm, plump, and structurally sound.

The Role of the Central Vacuole

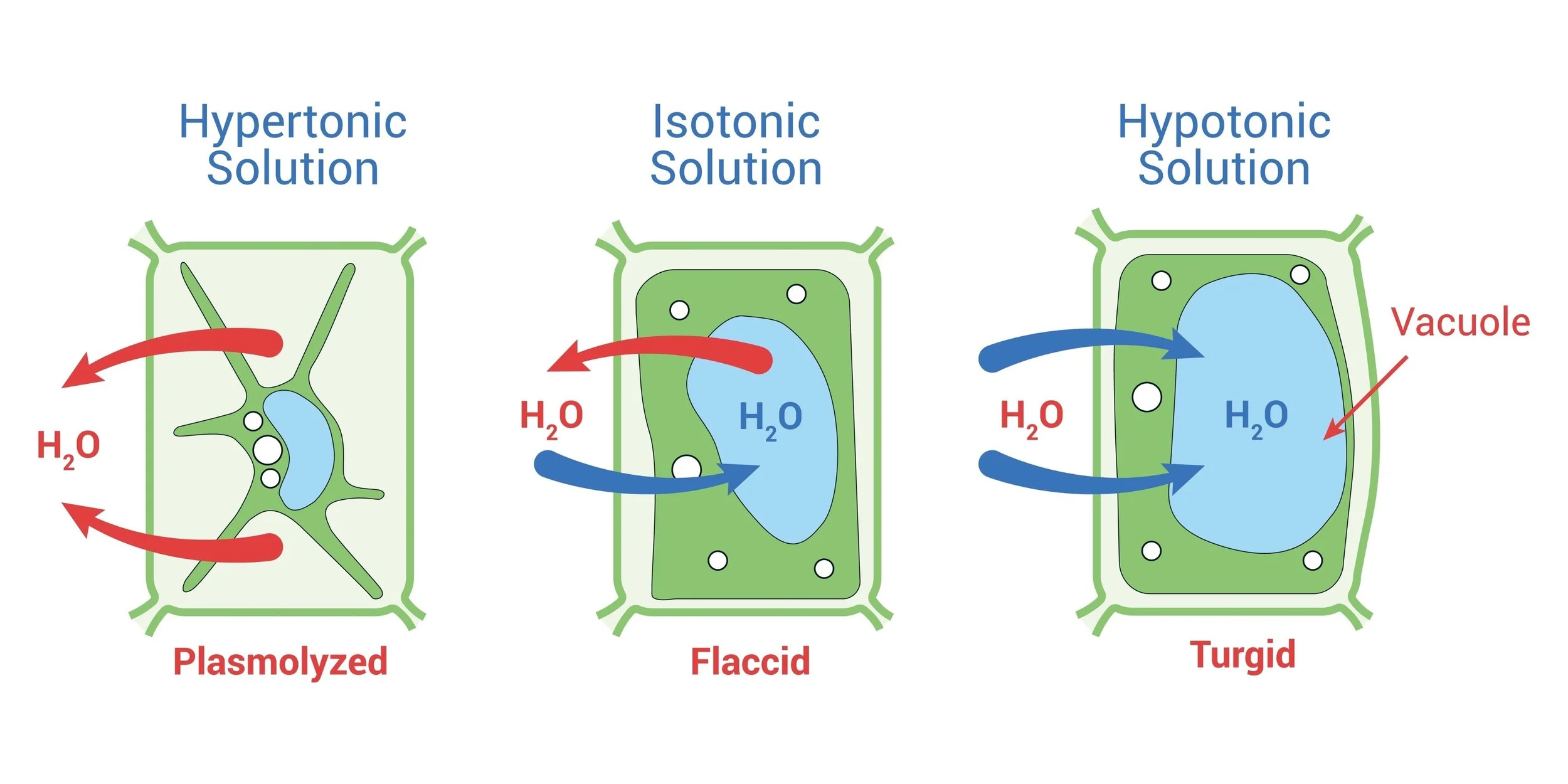

Every plant cell contains a large organelle called the central vacuole. Think of this as a biological water balloon. When you water your plant, the vacuole fills up via osmosis, expanding until it presses against the cell wall. This pressure is what keeps a leaf horizontal so it can maximize its surface area for sunlight.

When the plant loses water—either through transpiration or lack of supply—the vacuole shrinks. The cell membrane pulls away from the wall (a process called plasmolysis), and the plant physically sags.

The Defence Mechanism of Leaf Curling

Curling is a more sophisticated physiological response than drooping. It is an active attempt by the plant to survive environmental stress:

Inward Curling: By rolling its leaves inward, the plant creates a micro-environment of higher humidity near its stomata (the pores on the underside of the leaf). This reduces the concentration gradient, slowing down water loss.

Downward Curling (Epinasty): This is often a sign of "wet feet" or ethylene gas buildup. The plant is essentially trying to shed excess water or respond to root stress by changing the angle of its leaves.

Distinguishing between a plant that is thirsty and one that is suffocating from overwatering is critical to maintaining proper cellular structure.

| Visual Signal | Biological Mechanism | The Solution |

|---|---|---|

| General Drooping (Dry Soil) | Loss of Turgor Pressure in the central vacuole. | Deep watering; check for hydrophobic soil (water running off). |

| General Drooping (Wet Soil) | Root Hypoxia; roots cannot uptake water due to lack of oxygen. | Stop watering immediately; aerate the soil with a chopstick. |

| Inward Leaf Curling | Stomatal Protection; reducing surface area to stop transpiration. | Move away from direct light/heat; increase ambient humidity. |

| Downward "Clawing" | Nitrogen Toxicity or Root Rot; internal hormonal imbalance. | Flush soil to remove excess nitrogen or check for dark, smelly roots. |

4. Stunted Growth: The Light and Space Connection

In the science of happy plants, light is not just a preference—it is the raw material for building biomass. Through photosynthesis, plants convert light energy into chemical energy (ATP) and sugars. If the "factory" isn't getting enough raw material, it shuts down production to prioritize survival over expansion.

The Physics of Light: The Inverse Square Law

Many gardeners believe that moving a plant a few feet away from a window won't make a big difference. However, physics says otherwise. Light follows the Inverse Square Law, which states that the intensity of light is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the source.

Mathematically, if you move your plant from 2 feet away from a window to 4 feet away, the distance has doubled, but the light intensity has dropped to one-fourth ($1/2^2$) of its original strength. This dramatic drop in "fuel" is often why plants in the corner of a room seem to enter a state of permanent hibernation.

Hormonal Control: The Biology of Auxins

When a plant doesn't get enough light, it often becomes "leggy" or "stretched." This is a biological phenomenon called etiolation, driven by a class of hormones known as auxins.

Auxins are responsible for cell elongation. They are light-sensitive and tend to concentrate on the shaded side of the stem. This causes the cells on the "dark side" to grow longer than those on the light side, physically pushing and bending the plant toward the light source. While this is a brilliant survival tactic in nature to reach the canopy, in a home, it results in weak, spindly stems that cannot support their own weight.

The Root-Bound Barrier

Space is the second half of the growth equation. When a plant becomes "root-bound," the roots begin to circle the bottom of the pot. The plant senses this physical limitation and sends chemical signals (often using the hormone abscisic acid) to the rest of the plant to halt leaf production.

This prevents the plant from growing a "top" that the "bottom" can no longer support with water and nutrients.

A plant’s physical stature is a direct reflection of its access to photons and the freedom of its root system to explore the substrate.

| Growth Signal | Scientific Reason | The Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Leggy" Stems | Etiolation; Auxin accumulation on the shaded side of the stem. | Increase light intensity; rotate the plant 90 degrees weekly. |

| No New Growth | ATP Deficit; the plant is in a "maintenance only" energy state. | Move closer to light (Inverse Square Law) or provide supplemental LEDs. |

| Small New Leaves | Resource Scarcity; insufficient sugars to build full-sized tissue. | Provide balanced N-P-K fertilizer and optimize light duration. |

| Roots Circling Surface | Physical Constraint; hormonal signals halting shoot expansion. | Repot into a container 2 inches wider; prune circling roots. |

5. Spots and Pests: Identifying External Threats

While light and water are environmental, pests and diseases are biological. A healthy plant has a "skin" (the cuticle) and an immune system, but when these are breached, the plant undergoes a dramatic physiological shift to protect its remaining tissues.

Fungal Pathology: The Spore and the Halo

Fungal infections, such as Leaf Spot or Powdery Mildew, usually begin when a microscopic spore lands on a damp leaf. If the humidity is high enough, the spore germinates and sends out "roots" called hyphae that penetrate the leaf surface to steal sugars.

One of the most telling signs of a fungal infection is a brown spot surrounded by a yellow ring or "halo." This halo is the plant’s hypersensitive response (HR). The plant intentionally kills the healthy cells immediately surrounding the infection to create a "firebreak," starving the fungus of nutrients and preventing it from spreading further.

Sucking Pests and the Honeydew Effect

Pests like aphids, scale, and spider mites are more than just a nuisance—they are "biological vampires." They use specialized mouthparts called stylets to pierce the plant's phloem (the tissue that carries sugar).

Spider Mites: These cause "stippling"—tiny yellow dots—because they drain the chlorophyll from individual cells.

Aphids and Scale: Because the sap in the phloem is under high pressure, these insects often take in more sugar than they can digest. They excrete the excess as a sticky substance called honeydew, which often leads to the growth of sooty mold.

Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR)

When a plant is attacked, it doesn't just sit there. It triggers Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR), a "whole-plant" immune response. When a leaf is bitten, it releases volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like jasmonic acid.

This chemical signal travels through the air and the plant's vascular system to warn other leaves to "toughen up" by producing bitter tannins or thickening their cell walls before the pests arrive.

Understanding these signals allows you to intervene with organic treatments like Neem oil before the plant's internal defences are overwhelmed.

| Visual Signal | Biological Pathogen/Pest | The Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Brown Spots with Yellow Halos | Fungal Pathogen (Gaining entry via high humidity). | Increase airflow; avoid wetting leaves; apply fungicide. |

| Fine White Webbing | Spider Mites (Tetranychidae); active in hot, dry air. | Wipe leaves with water/Neem oil; increase humidity. |

| Sticky "Honeydew" Residue | Aphids or Scale (Sucking phloem sap). | Wash with insecticidal soap; introduce ladybugs (predators). |

| White "Dusty" Coating | Powdery Mildew (Surface fungal growth). | Mix 1 part milk to 9 parts water and spray to alter pH. |

Become a Plant Whisperer

Decoding the science of happy plants transforms you from a casual owner into a proactive caretaker. By recognizing that a yellow leaf is a nutrient "harvest" and a drooping stem is a "cellular collapse," you can make precise adjustments rather than guessing. Your garden is always speaking; you just need to know how to look for the clues.

Developing a consistent weekly observation habit is the single most effective way to ensure your plants thrive for years to come.

At Gauld Nurseries, we understand that a "happy plant" starts with superior genetics and a robust root system. Mass-produced plants often suffer from "transplant shock" or hidden pests because they are grown for speed, not longevity. By choosing plants that have been expertly acclimated to the Niagara climate, you give your garden a biological head start.

Expert-Grade Soil & Amendments: We stock the specific mineral-rich soils and chelated nutrients discussed in this guide to prevent "nutrient lockout."

Niagara-Hardy Stock: Our plants are selected for their resilience against local humidity shifts and temperature fluctuations.

Pro-Level Advice: Our team can help you identify mobile vs. immobile nutrient issues in person—just bring us a photo of your leaves!

Investing in professional-grade plants and nutrients is the most effective way to ensure your garden remains a thriving, low-stress ecosystem.

“We were back at Gauld Nurseries for the second time before Christmas to pick up a 4 or 5 foot potted Christmas tree that we could plant after at a recreational property. Jack spent a lot of time with us to ensure we were happy with our experience so we would be enticed back. Great conversation about growing trees from seeds and other native species we might consider. Would we go back? Absolutely.”